A few months ago I happened to casually touch on the question of inflation, and mentioned that while it may be easy to assess over short periods, compositional changes render it hard to interpret over time [Standard Errors]. Well, it turns out I may have been overly optimistic about how easy it is to interpret inflation data over short periods!

Inflation phobia is all the rage now, with the Fed promising to tamp down on inflation via rate hikes. I do not claim to know the right level of interest rates to maintain a healthy economy, and this newsletter is not the right place to look for it. However, I do think a big part of the panic and fear in the discourse is due to the fundamental uncertainty in what’s happening, and a big part of that is due to measurement. We’re seeing prices go up but it’s not clear exactly what is happening and as a result, how to think about the problem and solutions.

I’m well aware that the Bureau of Labor Statistics is releasing Consumer Price Index (CPI) data today, and this post is written in advance of that. I don’t think it matters - the key point I’m hoping to make is that inflation is in some sense invisible, and CPI captures an aspect of it but not the “truth”. There is enough wiggle room and uncertainty around Covid dynamics to crack some daylight between the phenomenon and the measurement, and that’s causing people to freak out.

Where are prices higher?

By all measures, the United States is facing fast increases in prices. The year-on-year increase in prices in December was 7%, the fastest in decades [Bloomberg].

It is generally described as red-hot inflation, which is not good. Inflation is bad for two main reasons: first, if prices increase without commensurate increases in wages, then real standards of living go down. Simple as that. The second is because uncontrolled increases in prices create poor inflation expectations which in turn causes pathological behavior to spend before your money becomes worth less. This in turn causes shortages, which sellers respond to price increases which causes your dollars to be worth less and, well, it’s easy to see how this all ends in tears. That’s why economists, particularly of the Chicago school like the late Milton Friedman, stress the centrality of expectations as both a consequence and method of controlling inflation [Brookings]. More on this later.

However, the internals of the inflation are very strange, and another way to look at that shocking December number is simply “gas is expensive” [BLS].

Expensive gas is quite bad for consumers but it’s hard to look at that and say “okay, that’s inflation”. Firstly, because gas prices are set in a global market so there’s no specific US information there. Secondly, because there is a base effect - the prior year was December 2020, when gasoline demand was much lower due to an ongoing global pandemic you may be aware of. All right, you might say, but other prices are also much higher (5.5% when excluding food and energy).

Well, it turns out that a lot of the rest is just used cars. Due to a semiconductor shortage caused by car companies cutting car production in 2020, new cars are hard to find. This has led to a squeeze in the used car market, where prices have exploded - and used cars are weighted heavily in the consumer price index [CNBC].

Two idiosyncratic supply squeezes are contributing roughly half of the headline increase in prices. And the same dynamic keeps popping when you look at other goods and services. Flight prices are rising fast now, in large part because of oil price increases, alongside the margin pressure from the plunge in more profitable international travel [Forbes]. Coffee prices are rising due to bad weather in Brazil [Bloomberg]. Any market you look at (and it’s “fun” to read about random ones), you see price increases stemming ultimately from Covid-created shortages in real materials or labor.1

Crucially, these huge price increases are also happening in economies with very different macroeconomic contexts than the United States! This dynamic is quite similar to the stories about labor shortages in the United States in 2020-22 blaming labor shortages on expanded unemployment insurance or stimulus checks, which blew right past the fact that you could read the exact same stories about labor shortages in any developed country which all had very different fiscal responses to the pandemic. Headlines like this coming out of the Eurozone should make you skeptical that the explanation is to be found in the policies of the US:

So it’s indisputable that prices are up and real incomes are down, which is not good. However, that still leaves open the question of whether it is clarifying or enlightening to call this “inflation”.

Expectations Aren’t There

The really big concern about inflation, as I alluded to above, is the role of expectations. Inflation is ultimately forward-looking, and belief that the currency’s value is dropping motivates pathological and destructive behavior.

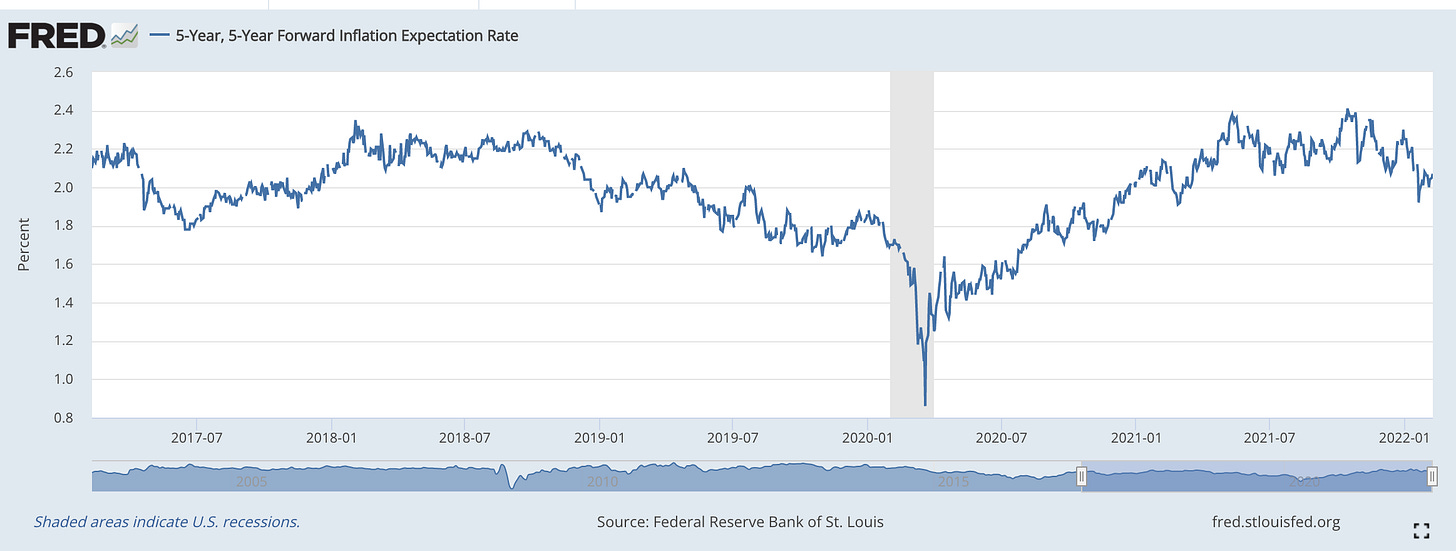

And yet when you look for evidence of increasing inflation expectations in the US, particularly of the runaway variety economists most fear, it just…isn’t really there. The Michigan Consumer Survey is high but no higher than the summer of 2008 [St. Louis Fed], a surge which was likely driven by a historical spike in gasoline prices [Treehugger]. The “five-year breakeven”, the expected five-year inflation average from traders with billions on the line, is right in line with the pre-covid trend at 2.2% [St. Louis Fed]:

And last but certainly not least, you see consumers reacting to rising prices by delaying spending rather than front-loading spending. An expectations-driven inflationary spiral has very strong predictions about how people will behave to rising inflation expectations: spend now. And yet across some of the most impacted categories consumers are doing the opposite. Price increases has buyers delaying, rather than trying to rush in [Boston Agent]. A record-low number of people say now is a good time to buy a house [CNBC]. Shoppers are delaying car purchases too [KBB]. All in all, people are behaving the opposite of how you might expect in an environment of rising inflation and rising inflation expectations.

The Map Is Not the Territory

The ways in which people are discussing inflation today is making a category error. Price indices are constructed in order to measure inflation, but they need to be clearly understood as a measurement instrument rather than the thing itself. A good index is one that will move upwards in the presence of the phenomenon, but this index can clearly move in the absence of the real phenomenon. To use an extreme example: a war in Ukraine would cause oil prices to explode upwards, which would have a huge impact on CPI, but there is no way for monetary policy to drive that oil price back down. Is that inflation?

I cannot claim to know what the Federal Reserve should do, but I think it is this apparent decoupling of the phenomenon and the measurement that is causing all the fear and loathing around inflation. Covid is something of an out of context problem for standard mental frameworks for inflation, and it’s disorienting and scary when the map and territory start to diverge.

I lean much more towards the “idiosyncratic Covid shocks” theory of price increases but I think the most compelling case for macroeconomic-driven inflation was given succinctly by economist Jason Furman [NYT]. To paraphrase: if there’s “freakish stuff” happening in every industry leading to price spikes…maybe they're connected.