Welcome to 2021! One of my resolutions for this year is to spend more time digging into the data and writing more deeply about my adoptive city, Los Angeles. It is beautiful, ugly, weird, boring, fascinating, and last but not least offers the internal heterogeneity any good data jockey craves.

In the recent weeks, tragedy has overtaken Los Angeles. LA is facing a crisis that appears every bit as bad as that which struck New York in the spring and is continuing to get worse [CNN]. This outbreak poses a seeming paradox - the crisis is bad and getting worse, despite restrictive public health policies that California and LA County have had in place since the spring.

The Los Angeles outbreak does appears to be rooted in policy decisions, but not policies about public health at all. Instead, it is rooted in the disastrous land-use and housing policies that have driven its ruinously high cost of housing and driven the working poor into the most overcrowded housing in America. These crowded homes, full of essential workers, were an epidemiological power keg just waiting for a match.

Coronavirus is not a morality play

If you happen to have spent any time on social media over the past year (I wouldn’t recommend it), the rhetoric about behavior and choice is often inflammatory and moralizing. Those who hold more communitarian ideals will name and shame those who are actively socializing or disdaining the use of masks [Wired]. Those with more individualistic ideals will conversely react aggressively against what they perceive as infringements on their individual liberty.

One might come away from this discussion thinking that the spread of Covid-19 is mainly due to people behaving ‘responsibly’ or ‘irresponsibly’. I don’t think that this particularly reflects the data, nor does it explain the dynamics that have punished Los Angeles with this horrible outbreak. When we look at where in Los Angeles the outbreak is the worst, it is not evenly distributed across the metro area but is highly concentrated, with the hardest-hit areas seeing levels of infection 5 or 6 times worse than other areas. We might hypothesize that the highest infection rates in the wealthier western side of the city where people can travel or eat at restaurants. But here’s the actual map of Covid-19 rates per 100,000 in LA County [LADPH]:

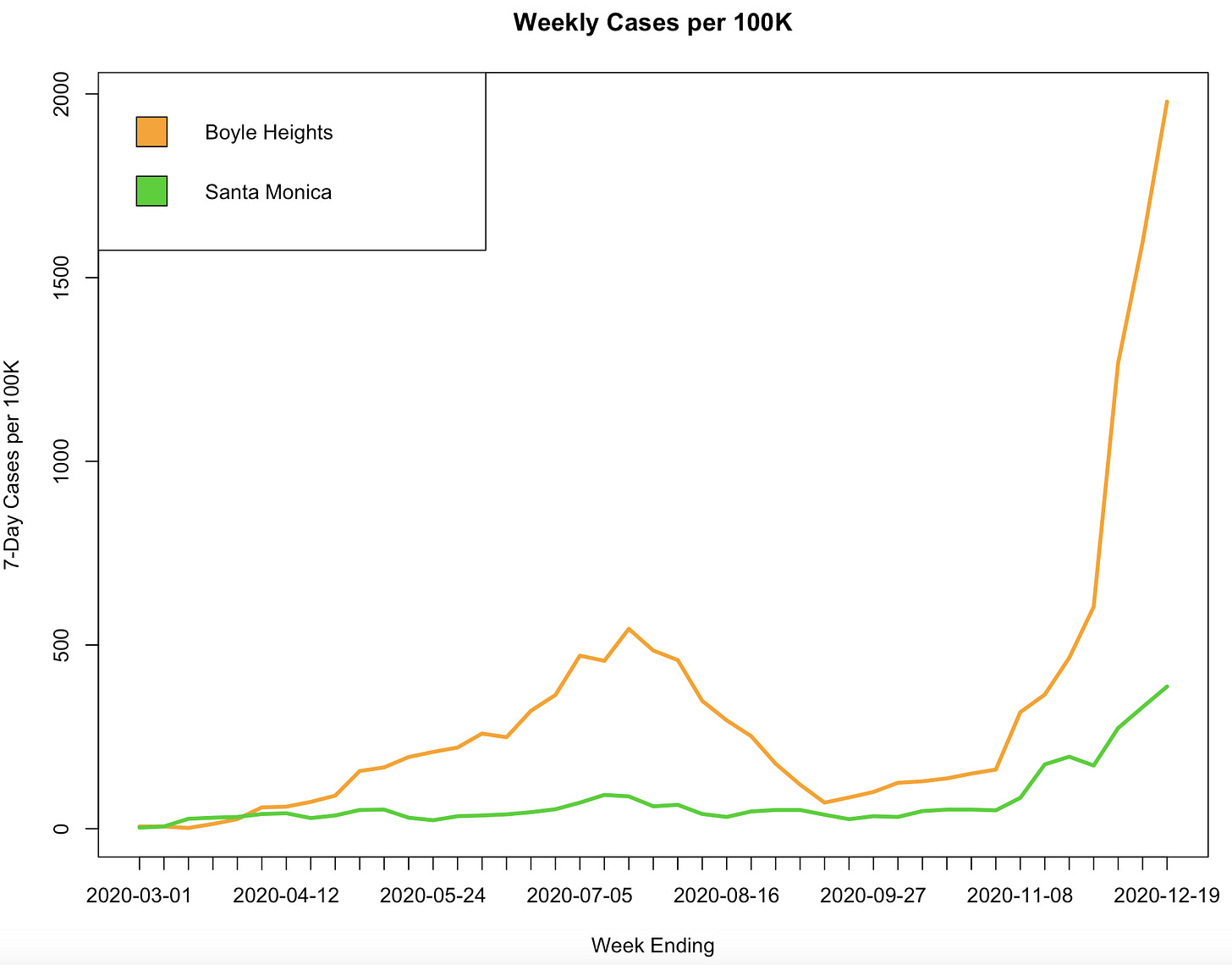

The regional pattern is stark, and summed up in the story of two roughly comparable areas. Santa Monica and Boyle Heights are roughly the same size, close to 90,000 people, and roughly the same population density at around 12,000 people per square mile. Both are quite dense urban areas by US standards, and both are part of LA County and governed by the same rules from the County Public Health Department. However, Santa Monica is wealthy and white while Boyle Heights is poor and almost entirely Latino. Boyle Heights is also suffering from a Covid-19 outbreak that is FIVE TIMES as bad as Santa Monica and getting worse far faster:

The evidence of the map doesn’t mesh with the idea that the spread of coronavirus is driven primarily by people traveling or going out to eat. It also suggests the course of the outbreak in the County isn’t driven by public health policy, as both neighborhoods are subject to the state of California and the Los Angeles County Health Department. Furthermore, there weren’t any major policy regime changes in between the late summer and late fall. Instead the map of case prevalence mirrors a mental map every Angeleno has in their head: poverty. [The Opportunity Atlas]

While we could do some complicated regression analysis if we chose, it frankly isn’t required. The visual pattern is stark and obvious - the Covid-19 pandemic in Los Angeles is deeply concentrated in the (poorer, African-American and Latino) central and eastern areas of the city. This makes it hard to accept at first glance a theory of the disease that is primarily about individuals making risky choices for frivolous reasons - if that was really the biggest cause, we’d expect the spread to be concentrated in the parts of the city where people have the means to make those choices.

Instead the disease closely tracks crowded housing in impoverished areas. Los Angeles is plagued by extremely expensive housing, which seems to sit at the center of every civic ill and Covid-19 is no exception. Poor households in LA live in very crowded houses that often have many more residents than bedrooms, where a single infected resident cannot isolate from the rest of the household. An analysis by Cal Matters this summer [Cal Matters] found that there is a strong and direct relationships between how crowded a neighborhood’s housing is and how badly the first wave struck.

Poor Angelenos are doubly-exposed between their housing and their jobs. The same Cal Matters analysis found that “two-thirds [emphasis added] of Californians who live in overcrowded homes are essential workers or live with at least one essential worker”. The working poor in Los Angeles are much more likely than the work-from-home class to contract Covid-19 at their job sites, and once infected to spread it to their immediate household. Unfortunately, those essential workers need those jobs more than ever because the Covid-19 recession has been a disaster for low-wage workers in Los Angeles. Employment for low-wage workers has cratered in a way that seems pretty unrelated to any “lockdowns”, as it has not recovered even as restrictions were loosened in the summer and fall [Track the Recovery].

This is bigger than all of us

It’s easy to fall prey to a fallacy of composition [Wikipedia] error when thinking about the spread of Covid-19. If you are lucky enough to hold a job where you are able to work from home, going to a bar or hopping on a plane would be two of the highest-risk things you could do. It’s easy to slip from that into thinking that the spread of infection is being driven primarily or solely by individual decisions to take risky actions.

Instead, the spread of Covid-19 in Los Angeles appears to be primarily driven by policy decisions. The crucial policy decisions are not the public health decisions we read about in the news, but the disastrous housing policies made over the past few decades that have crammed poor residents into fatally overcrowded homes.

This is not to say that this is the be-all-and-end-all theory of why Covid-19 has gotten so bad in the United States. A theory centered around individual decision-making or policy failure might well explain the terrible outbreaks in North Dakota, where there is very little public health response and poor individual compliance. That’s the frustrating incompleteness of social science, where no causal explanations are ever complete but may be differently true in different places at different times.

Stay home and stay safe!

Further reading and links:

Great analysis. I see this on the ground.